Dungeons & Dragons: The Name, the Legacy, and the Chaos Along the Way

You’ve probably heard of Dungeons & Dragons, whether through a podcast, a Stranger Things episode, or that one coworker who always talks about their gnome bard. When people say “D&D,” they might also call it “DnD,” “5e,” or just “that game with dice and dragons.”

These days, a lot of people use “D&D” as a kind of catch-all for tabletop role-playing games (TTRPGs). If someone says they’re “playing DnD,” they might be using Dungeons & Dragons rules, or they might be playing something totally different like ShadowDark, Dragonbane, or Monster of the Week. For newcomers, D&D is just the word they’ve heard before, and that’s okay.

If you are a longtime player, be kind. The feelings they’re chasing are the same ones that brought us all to the table in the first place. The point is that they’re showing up to tell stories together.

So… what actually is Dungeons & Dragons? Where did it come from? And why does it seem like it’s always surrounded by some kind of drama?

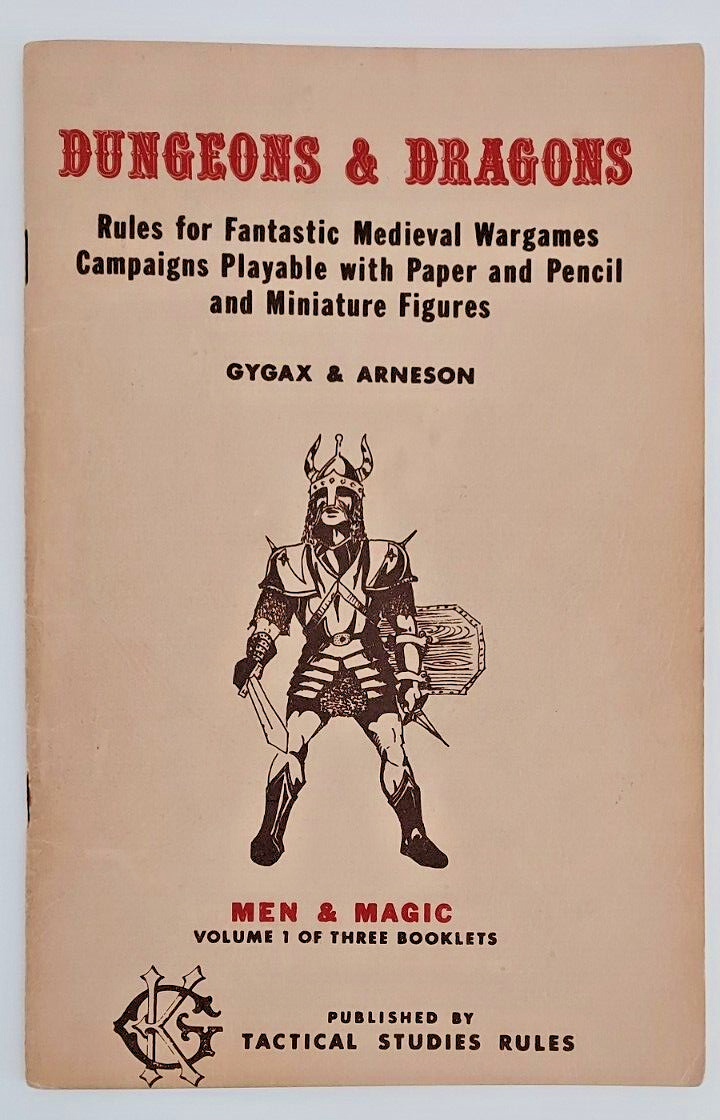

Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson

TSR originally stood for Tactical Studies Rules, the company Gygax and his partners founded to publish the original D&D rules in 1973. Later on, the name was shortened to just TSR, Inc.—a company that went on to become a pillar of early tabletop gaming until its acquisition by Wizards of the Coast in 1997.

The Origin Story: How It All Began

In 1974, Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson created a game that blended miniature wargaming with fantasy storytelling. The result was Dungeons & Dragons, published by TSR.

It was clunky, crunchy, and hard to learn, but totally unique. Those early booklets? Hand-assembled. Mail-ordered. And deeply influential.

Note: While Gary Gygax is the name most often associated with the creation of D&D, he wasn’t alone. Dave Arneson, often overlooked, co-developed the earliest ideas of character-driven fantasy adventures, what we now think of as the dungeon crawl. Though Gygax refined the system and brought it to market through TSR, Arneson’s Blackmoor campaign was arguably the first true TTRPG. Their partnership was rocky and short-lived, but together, their work laid the foundation for everything that followed.

When Gygax and Arneson were building what would become Dungeons & Dragons, they weren’t pulling ideas out of thin air, they were drawing on a stew of influences that included:

J.R.R. Tolkien – The DNA of The Lord of the Rings is all over early D&D: elves, dwarves, orcs, rangers, wizards, and magic swords. Gygax often downplayed Tolkien’s impact (mostly for legal reasons), but let’s be real… it’s there. The ideal adventuring party is the Fellowship of The Ring

Pulp fantasy authors like Robert E. Howard (Conan), Michael Moorcock (Elric), Fritz Leiber (Fafhrd & the Gray Mouser), and Jack Vance (whose quirky, limited-use magic system inspired D&D’s iconic “Vancian” spellcasting).

Miniature wargames – Especially Chainmail, a medieval fantasy skirmish ruleset co-authored by Gygax. D&D was born as an extension of that system, adding roleplaying elements on top of tactical battles.

Westerns, horror, sci-fi, and classic myths – D&D quickly grew beyond medieval fantasy, pulling monsters and ideas from all over genre fiction.

D&D didn’t invent the fantasy genre, it built a playable framework out of the stories people already loved.

Controversy & Growth: The Satanic Panic Years

As D&D gained popularity in the late 1970s and early 1980s, it also gained something else: national attention, and not the good kind.

Parents, churches, and media outlets began to paint Dungeons & Dragons as dangerous. They claimed it promoted:

Witchcraft and devil worship

Violence and suicide

Occultism and satanic behavior

At the height of this panic, news reports, talk shows, and even made-for-TV movies warned of teens vanishing into fantasy worlds and never coming back. One of the most infamous cases was the disappearance of James Dallas Egbert III, a college student whose story was wrongly linked to D&D and sensationalized into the film Mazes and Monsters starring a young Tom Hanks.

The truth? D&D was no more dangerous than a game of Monopoly.

But the backlash had an unexpected side effect: it gave D&D mystique. For some players, it became a rebellious, underground pastime. TSR even leaned into it, releasing darker settings like Ravenloft, Planescape, and Dark Sun that embraced the gothic and weird.

And ironically, it was often the misunderstood nature of D&D that led people to fall in love with it.

What was intended to scare people away actually pulled more folks in.

Enter Wizards of the Coast

By the mid-1990s, TSR was in financial trouble. In 1997, the company was purchased by Wizards of the Coast (WotC), a rising star in the gaming world thanks to their massive hit Magic: The Gathering.

Wizards was more than just a publisher, they were building a brand, a culture, a world. And they weren’t just responsible for Magic or D&D, they also helped bring Pokémon to the U.S. trading card scene, which made them a cornerstone of kid culture in the late ’90s and early 2000s.

With D&D under its wing, Wizards released 3rd Edition in 2000. With 3rd Edition, Wizards introduced the d20 System, a game-changer in more ways than one. Instead of juggling different mechanics for every kind of action, everything now revolved around a single core rule: roll a d20, add modifiers, and try to beat a target number. This unified system made the game easier to learn, faster to run, and far more adaptable. It also set the stage for an explosion of third-party content, since the rules were released under the Open Game License (OGL). Other publishers quickly began building entire games off the same foundation, turning the d20 into a kind of universal language for fantasy tabletop gaming.

It was the beginning of D&D’s modern era, and a moment that shaped the hobby forever.

The Editions: A Quick Breakdown

There have been many editions of DnD over the years, each with it’s own tone, mechanics, and feel. Here’s a rundown of the mainline versions:

| Edition | Year | What Changed |

|---|---|---|

| 1st Edition | 1974 | The OG. Built from wargaming roots—very open-ended, super DIY, and rough around the edges. Think rules-light, imagination-heavy. |

| 2nd Edition | 1989 | Streamlined mechanics, tons of official campaign settings (like Forgotten Realms and Ravenloft). Introduced “THAC0” and leaned into roleplay over pure combat. |

| 3rd / 3.5 Edition | 2000 / 2003 | Huge mechanical overhaul. More customization, skills, feats, multiclassing. Introduced the d20 System and sparked a third-party publishing boom thanks to the OGL. |

| 4th Edition | 2008 | A bold shift. Tight balance, grid-based combat, and powers for every class. Some loved its tactical depth, others felt it lost the open-ended story feel. |

| 5th Edition (5e) | 2014 | The “gateway” edition. Simplified rules, emphasis on narrative and accessibility. A perfect blend of story, action, and flexibility. |

| 5e (2024 Update) | 2024 | A modern refresh of 5e. Backward compatible with updated mechanics and digital support under the “One D&D” initiative. |

The OGL Debacle or How to Lose a Fanbase in 3 Days or Less

In early 2023, Wizards of the Coast found itself in a PR inferno of its own making.

The issue? The Open Game License (OGL), a legal framework first introduced with 3rd Edition that allowed creators to publish compatible content without fear of lawsuits. This license helped launch third-party publishers, community creators, and indie hits like Kobold Press, Critical Role’s Tal’Dorei, MCDM, and countless homebrew supplements on platforms like DMs Guild and DriveThruRPG.

It was, in short, a pillar of the modern TTRPG ecosystem.

But then leaked documents revealed that Wizards was planning to:

Revoke the original OGL 1.0a

Introduce a new, more restrictive license (OGL 1.1)

Require royalty payments from successful creators

Claim greater control over published third-party content

The backlash was immediate, and brutal. Fans, creators, and even some longtime D&D supporters called it out for what it was: a blatant cash grab that threatened the very community that had kept D&D alive and thriving for decades.

The hashtag #OpenDND trended. Publishers announced plans to move away from D&D. Thousands canceled their D&D Beyond subscriptions in protest.

Eventually, WotC issued a public apology and walked it all back. They released portions of the 5e System Reference Document (SRD) under a Creative Commons license, which helped calm things down. But the trust? That was harder to recover.

The good news? The OGL drama sparked a wave of creative independence across the TTRPG landscape:

Kobold Press announced its own game system, Tales of the Valiant

MCDM (Matt Colville’s company) started building a system from scratch

ShadowDark, Black Flag, and Knave 2e gained massive attention

The ORC License (Open RPG Creative License) was introduced by Paizo and allies to ensure open, protected publishing rights

D&D may still be the biggest name in the space, but it no longer owns the table.

D&D in Pop Culture: From Basement to Blockbuster

Over the last decade, Dungeons & Dragons has gone from nerdy niche to full-blown mainstream. And a huge part of that is thanks to the rise of actual play shows, where people stream or record themselves playing TTRPGs.

The most famous of these is Critical Role, a show that began as a group of voice actors playing in their living room and turned into a media empire with:

Multiple campaigns watched by millions

A successful animated series on Amazon (The Legend of Vox Machina)

Its own publishing imprint (Darrington Press)

Other standout actual play groups like Dimension 20 (Dropout), The Adventure Zone, Not Another D&D Podcast and (my personal favorite) Tales From The Stinky Dragon have shown that TTRPGs can be funny, emotional, cinematic — and deeply, addictively bingeable. Add to that the surge of content on Twitch, YouTube, TikTok, and podcasts, and D&D has become something entirely new: a performative storytelling medium.

For many new players, their first experience with D&D isn’t playing, it’s watching others play really, really well.

D&D on the Big Screen and Beyond

The popularity boom didn’t stop with livestreams. D&D has:

Popped up in shows like Stranger Things, Community, and The Big Bang Theory

Inspired licensed comic books, novels, merch drops, and streaming specials

Hit movie theaters with Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves (2023), which charmed fans and newcomers alike by leaning into the game’s tone: heartfelt, chaotic, and just a little goofy

Netflix is in active development of a live-action D&D show

And all of this has helped shed the old stereotypes. D&D isn’t just for bearded dudes in basements anymore (though they’re still welcome). It’s for:

Teens with notebooks full of lore

Queer creators building inclusive fantasy worlds

Parents introducing their kids to the magic of imagination

Streamers performing their hearts out for millions of fans

D&D didn’t change overnight. It just finally found the spotlight it always deserved.

So… What Is D&D Now?

Dungeons & Dragons is… a lot of things.

It’s a game, yes, but it’s also a brand, a storytelling tool, a pop culture icon, and for many, a gateway into a broader hobby that’s more diverse and creative than ever before.

For some, it’s Friday night with friends and snacks. For others, it’s performance art, podcast fuel, or even a way to process real emotions through fictional characters. For kids, it’s often the first time they realize they can shape a story. For adults, it’s a much-needed escape — and sometimes a lifeline.

Loving D&D doesn’t mean loving everything about D&D, and that’s okay.

But D&D is also a corporate product, owned by Wizards of the Coast and Hasbro. That means the game is influenced by market trends, monetization goals, and executive decisions, not just player passion. And that tension shows.

It’s not unusual to find players who adore the game, but are frustrated with the company behind it.

D&D is the doorway, but it’s not the whole house. You can walk through and stay awhile, or you can find your way to another room entirely.

Dungeons & Dragons has changed hands, survived controversies, and reshaped itself over the decades. But at its core, it’s still about storytelling, imagination, and shared experience. You don’t have to love every edition or agree with every decision, but there’s no denying its impact on storytelling, creativity, and geek culture.

Wherever you land, it’s all part of the same adventure. Be curious. Try something new. And as always, be careful out there.